Sproutward Bound

A nourishing jar-to-table adventure.

At first glance, it hardly looks promising. One tablespoon of the “spicy seed mix” from my local food coop barely covers the bottom of a glass jar I’ve pressed into service to sprout seeds and beans. The jar, one of a few I inherited years ago, is from a set of one-quart Ball® glass canning jars my mother, Carmela, used back in her home canning days in Wenatchee, Wa.

Despite this modest beginning I am optimistic. After soaking in water overnight, I dutifully drain the water through the mesh lid, rinsing once in the morning and again in late afternoon. By the next afternoon after the second rinse, I take a close look and sure enough, the tiniest of white “tails” have emerged from the seeds!

Game ON.

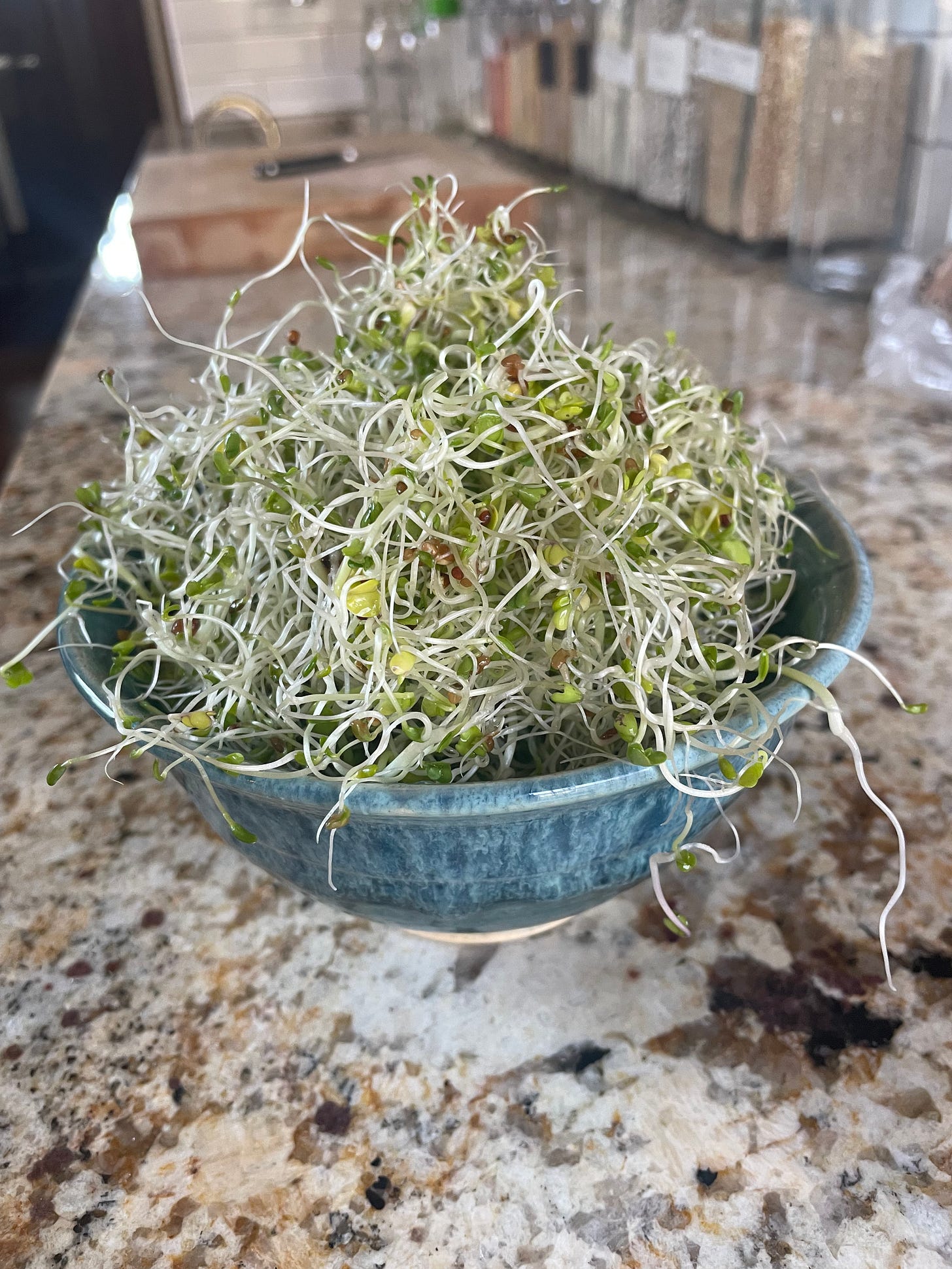

These tiny signs of successful germination will soon lengthen, each with the botanical determination to become fully developed plants. Before long, seed leaves will have appeared and turned vivid green. The vigorous, chlorophyl-rich sprouts that started as a tablespoon of seeds will have developed into a mass of fresh vibrant sprouts that presses against the sides of the jar that at first appeared comically oversized. Often, I’ll need to divide the exuberant crop into two jars, so the expanding mass has room for the final growth spurt before deeming them ready to “harvest”.

This seed-to-edible-delight transformation is truly amazing. But what is going on here?

According to Marvin Pritts, former chair of Cornell University Horticulture Department, when temperatures are warm enough and water is available, a seed that’s been kept sufficiently dry and/or cold, will readily absorb the water, and begin to swell. Metabolic processes (such as the conversion of starch into sugar) kick into gear, the seed is jolted out of its dormancy, and the embryo begins to grow, first by extending a root—the little white tails that got me all excited—downward and then a shoot upward. Of course, with seeds being in a jar and not planted in soil, up might be down and down might be up, but I digress.

On around day three, tiny pale leaves emerge. As Marvin explains, “these first leaves are full of a chlorophyll precursor”. Once exposed to the natural, even dim, winter light of my kitchen the precursor is activated, and the tiny leaves turn a vibrant green. “After light exposure”, Marvin describes, “cotyledons (the embryonic leaf in seed-bearing plants) begin to synthesize chlorophyll. This step involves at least 17 different enzymes. Not a simple process.”

Aside from engaging in a horticultural wonder in my own kitchen, why sprout your own seeds? Here are my top four reasons, from the personal to the global.

1. Taste and freshness

As anyone who sprouts seeds at home will attest, there are no fresher greens to be had throughout the winter and early spring. Given the variety of seeds, beans and grains that lend themselves to sprouting, there’s a rich variety of flavors and textures to be enjoyed. The taste of alfalfa sprouts is described on the Specialty Produce website as a “mild, nutty, and subtly sweet flavor with fresh green nuances.” I think that hits the mark, but that’s just straight alfalfa sprouts. In my stock of seeds, I have a mix that has alfalfa, plus both radish and broccoli seeds. The radish sprouts add a particularly peppery zing, and the sprouted broccoli seeds add nice crunch and more earthy flavor.

2. Nutrition and Health

Leafy greens provide some nutrients to good health, with kale, spinach, collards, and beet greens being particularly nutrient-rich.

How do sprouts compare with typical salad greens? From information readily available from USDA’s food composition database, FoodData Central, a few things jump out right away. First, alfalfa sprouts and green leaf lettuce provide essentially the same number of calories (not that anyone should be overly concerned about the calories in lettuce or sprouts!): 23 calories in 100 grams of alfalfa sprouts and 22 in an equivalent amount of lettuce. Second, “alfalfa seeds, sprouted, raw” provide much more protein than “lettuce, leaf, green, raw”, in fact sprouts have twenty-two times the protein content of green leaf lettuce (nearly 4 grams versus of .18 grams – per 100 grams). Alfalfa sprouts also provide more manganese and niacin than green leaf lettuce, are considered rich in B vitamins, vitamins C and E and contain several essential amino acids (the building blocks of protein).

If you’re like me, your sprout curiosity extends well beyond alfalfa seeds. Pulses, edible seeds from legume plants including lentils, mung beans, garbanzos, adzuki beans and peas, provide a hearty and chewy topping to salads, eggs, soups, and sandwiches. Nutritionally, there’s a clear argument for branching out as well.

A study published in 2021 in the journal Nutrients, evaluated the phytochemical content of selected sprouts (such as alfalfa, buckwheat, broccoli, red cabbage and others) not included the USDA database. The study and others describe potential health benefits of several biologically active compounds found in a variety of sprouts: antioxidant activity, antiviral activity, immune stimulation, antidiabetic activity, and protection against cancer.

What’s clear from research is that sprouts might be small, but their potential health benefits are mighty.

3. Cost

Sprouting makes sense for all of us on a food budget. There is a wide variety of organic sprouting seeds available in bulk. Alfalfa seeds might be the most common gateway seeds to sprout, but one can soon be led down a “sproutrageous” path to other seeds—broccoli, quinoa, radish, kale, clover—and then to (you knew it would happen) to a whole host of beans, grains, and legumes. Mixes of selected seeds and pulses are also available.

Whatever you decide, sprouting has been shown to be a cost-saving way to boost the nutrition. Going back to that gateway seed, alfalfa, one pound will set you back about $17.50. This seems like a substantial initial outlay until one considers that each tablespoon yields a quart jar of sprouts and there are about 40 tablespoons in a pound. That works out to less than 50 cents for a jarful of sprouts, to use in sandwiches, replace lettuce on a burger, as a topping for eggs at breakfast, or add to a hearty grain dish. The price tag for 10 ounces of boxed ready-to-eat salad mix grown in California, where most of the supermarket lettuces come from at this time of year, goes for over five dollars. At that price, sprouts make sense.

4. Environment

At a time when people are eager for ways to reduce their carbon footprint, one might consider switching out at least some leafy greens for sprouts. About a third of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions is linked to food. The production, packaging, and transportation fresh greens, especially those grown in the west and consumed in the east, is a notable contributor. What could be more local than a zero-food-mile substitute grown on the kitchen counter?

Granted, sprouts might be laughable replacement for leafy greens if a classic green salad is on the menu. Yet, it is reasonable to question the overall sustainability, of transporting a water-laden vegetable such as lettuce thousands of miles in refrigerated, diesel-powered 18-wheelers from a chronically water-challenged region to one that has abundant (at least for the moment) water resources. According to the produce manager at a nearby supermarket, the primary sources of salad greens—including head (iceberg) and leaf (romaine, butterhead, baby, and other leaf types)—sold in Northeast supermarkets during the winter, and largely throughout the year, are California or Arizona.

Even now, in early May, most of the salad greens found in this same supermarket were harvested, washed, chopped, chilled and boxed in protective plastic containers in California’s Salinas Valley before setting out across the country. According to one estimate, “over 1,800 truckloads of Iceberg and Romaine lettuce are being shipped weekly from the Salinas Valley”. Some of these trucks will head to a distribution warehouse in Rochester, NY, where they’ll be unloaded and then reloaded with other vegetables, in accordance with individual store orders, and then arrive in Ithaca.

Another reason to consider shifting at least some of your leafy green intake to fresh sprouts is to reduce your household food waste. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), about one-third of the entire food supply gets thrown away every year. That’s over 100 billion pounds, valued at well over 100 billion dollars. A spring 2023 survey of 2,000 randomly-selected U.S. adults conducted by the market research company, OnePoll and commissioned by America’s largest meal kit provider, HelloFresh, found that lettuce topped the list of foods that are most frequently thrown out.

Unless composted, or fed to pigs, these greens will likely end up in a landfill and add to food-waste generated methane, which is more than 28 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere. One more reason to consider sprouts as a fresh, hyperlocal, alternative well-traveled greens: because they’re so fresh, they’re gobbled up and rarely have a chance to go bad.

For many, a day just isn’t complete without fresh salad greens. Fine, I get that, but a good way to reduce your food miles, and thus your carbon footprint, is to purchase these lovely tender greens locally when they are available. Like right now! This past Saturday I was thrilled to see gorgeous red and green leaf lettuces at the Westhaven Farm stall.

I learned from Meagan, the Westhaven Farm CSA manager, that red and green leaf lettuce seeds had been planted in mid-February, germinated, and grown into seedlings on heated mats in a high tunnel until they were big enough to be transplanted in the ground in another high tunnel. Soon, she explained, the succession of leafy greens “coming from the nursery will be planted outside”.

In fact, as Meagan informed me in a follow up email, the first batch of lettuces were planted outside the day before I posted this newsletter. As if purposefully trying to make my mouth water, she wrote, “we also have a selection of baby greens including arugula, mixed salad greens (this includes baby kale, tatsoi & mustard greens), spinach and our microgreen mix. We will begin harvesting our salanova lettuce mix in 2-3 weeks as well. All of these items (except the spinach) we grow in weekly or biweekly successions through the fall, winter & spring to ensure a constant supply.”

So, the tender leafy green season will soon be in full swing in my area and in most of the Northeast and eastern seaboard. It’s time to shift our reliance on “the Salad Bowl of the World”, as the Salinas Valley is called, to local and regional farms.

Can’t be bothered?

If the idea of substituting some of your leafy greens with sprouts appeals to you but you’re not so keen on the daily tending, there may be a sprout farmer near you. In our area I know of one. Ellen Payton, owner of the nearby Dancing Turtle Farm in Freeville, NY is now in her 18th year as a sprout producer.

While her sprout farm started modestly, she quickly outgrew her home kitchen and invested in the equipment need to meet the standards for a commercial kitchen certification. Ellen now sells a wide array of fresh sprouts (as well as microgreens) at the Ithaca farmers market throughout the year. In total she produces about 60 pounds of sprouts per week in the winter, even more in the summer. A list of your local farmers market vendors is likely online and might include a sprout farmer. If your local market doesn’t have a sprout grower and such a venture is intriguing, resources on how to start a successful business are available through the cooperative extension service and support can be found from networks of sprout and microgreen producers.

Now that lettuces are once again in season here in the Northeast, I might give my sprout jars a good wash and put them away until next winter. I know when I start sprouting again, their amazing emergence, exuberant growth and fresh crunch will be as delightful as ever.

Love this! We make sprouts weekly - such a tasty and nutritious treat for salads, sandos, or on cottage cheese :)

Sprouting every day since you showed me how!